- 1854

Asa Fitch

Asa Fitch: An Emblem of RPI’s Bicentennial Legacy

In 1854, Asa Fitch, RPI Class of 1827, broke new ground by becoming New York’s first State Entomologist. But he didn’t stop at science. A Congressman and Senator, Fitch embodied the versatility and leadership that define an RPI education.

His pioneering career illuminates the depth and diversity RPI instills in its graduates. Whether it was the world of insects or the corridors of Congress, Fitch seamlessly navigated complex landscapes, epitomizing RPI’s mission to empower leaders capable of solving global challenges.

As we celebrate 200 years of educational excellence, Fitch’s multifaceted achievements stand as a monumental ‘first’ in our illustrious history. His blend of scientific acumen and political savvy captures RPI’s enduring commitment to shaping leaders for the multifaceted challenges of tomorrow.

- 1854

Eben Norton Horsford

Eben Norton Horsford was a member of the class of 1838. In 1854, he formed the Rumford Chemical Works with partner George Wilson. One of the company’s most successful products was baking powder, which revolutionized the production of bread and other baked goods. Their invention defines the product as we understand it today.

- January 21, 1857

The Commentator

In early 1857, RPI launched its first student newspaper, “The Commentator,” adding a significant chapter to its 200-year history. More than ink on paper, this two-page debut represented RPI’s commitment to nurturing not just technical minds, but articulate voices. In an era dominated by scientific milestones, “The Commentator” added a layer of complexity to RPI’s academic landscape. The paper offered a forum for student discourse, allowing burgeoning engineers and scientists to explore the power of the written word.

Today, as part of our bicentennial celebrations, we recognize this enduring ‘first’ as an emblem of RPI’s holistic approach to education. “The Commentator” continues to inspire a tradition of student journalism that complements our globally recognized STEM programs.

- 1861

Instituo Politecnico de Rensselaer

In a historic pivot to embody a global academic enclave, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute etched a noteworthy chapter in its 200-year odyssey by unfurling its first Spanish language publication in 1861. Titled “Instituto Politécnico Rensselaer,” this initiative wasn’t just about linguistic inclusion, but a beacon inviting intellectual synergy from beyond borders. With a resolute aim to magnetize international minds, Rensselaer’s outreach saw an enriching response from across South America. The ripple effect was profound: many of these enterprising scholars, armed with knowledge honed at RPI, became the architects of critical infrastructure back in their home countries. This narrative isn’t merely about a publication; it’s a testimony to RPI’s longstanding ethos of fostering a diverse, global cadre of thinkers and builders. As we retrospect, the 1861 milestone isn’t just a ‘first’ in linguistic endeavor, but a broad stride in RPI’s quest for global academic camaraderie.

- 1861

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

In 1861, the Rensselaer Institute underwent a transformative renaming to become Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). This historic rebrand was more than cosmetic; it reflected an expanded educational mission, extending the civil engineering degree from three years to four, elevating RPI into a leader in interdisciplinary STEM education. The change wasn’t just in title; it marked a shift in the Institute’s foundational ethos. Under Director Benjamin Franklin Greene, the Institute began calling itself RPI ten years before the name change was official. It was finally approved by the NYS Legislature on April 8, 1861.

As we celebrate our bicentennial, this defining ‘first’ stands out. The name Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute now serves as a symbol of our commitment to excellence and innovation, encapsulating our 200-year-old mission to prepare future leaders to meet global challenges.

- 1861

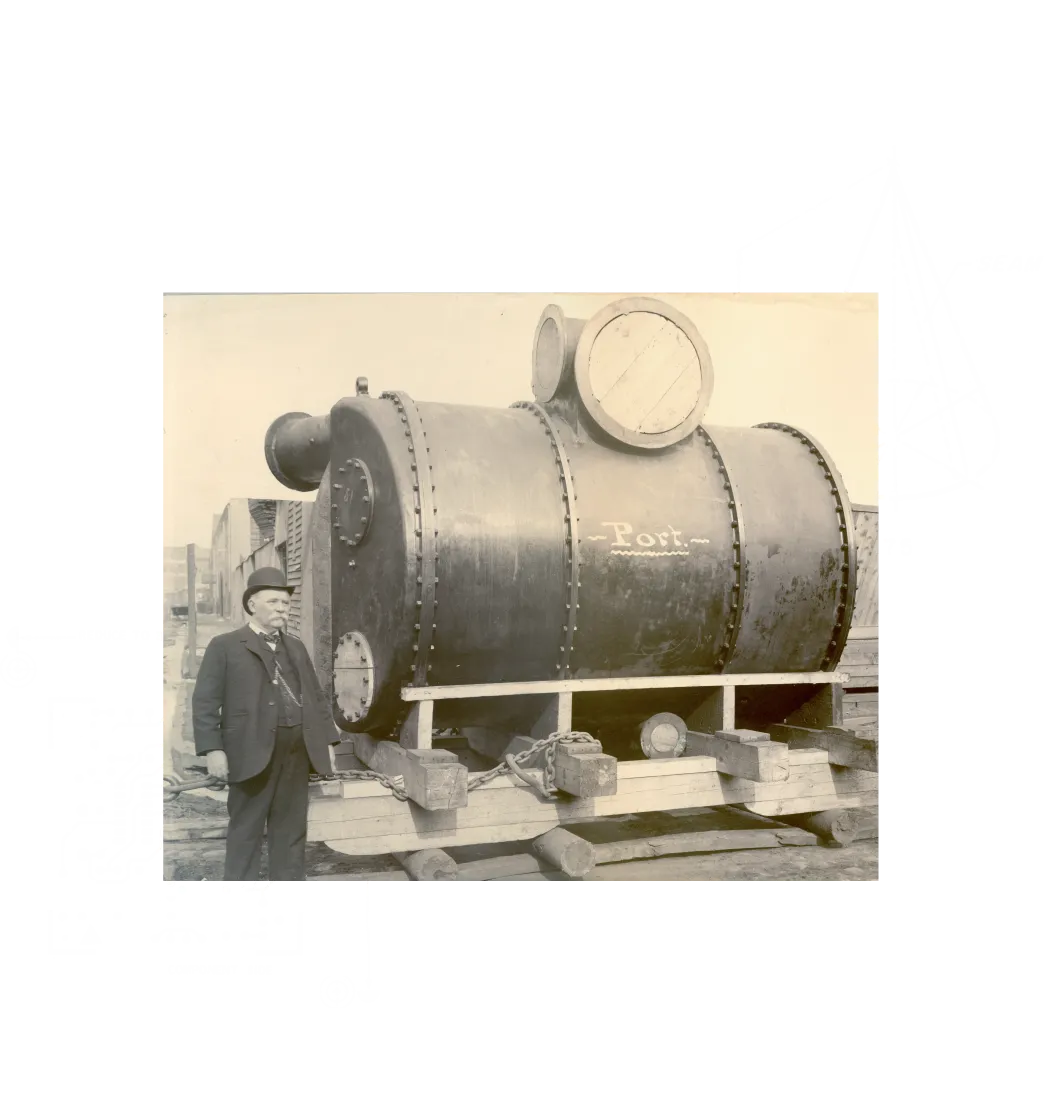

Burdett C. Gowing

In a remarkable juncture of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s 200-year narrative of innovation, a significant maritime transformation was spearheaded by Burdett C. Gowing, Class of 1861. Engineering a revolutionary contact surface condensor, Gowing charted a course into uncharted waters when his invention was first employed on a Union Navy ship, a Union Harbor Defense Ram. This wasn’t just a condensor; it was a gateway to unprecedented thermal power. By ingeniously converting seawater to steam and reconverting it to liquid, Gowing’s creation propelled the ship on thermal energy, veering away from the coal-dependency of the era.

This wasn’t merely an energy shift; it was a colossal stride in maritime operations, curbing time, labor, and financial expenditures. No longer did men tirelessly shovel coal for the vessel to voyage; Gowing’s condensor was the new power. A distinguished ‘first’ in RPI’s bicentennial legacy, embodying the Institute’s enduring tradition of engineering the future.”

- 1862

The Great Fire

In 1862, amidst the backdrop of a burgeoning urban sprawl, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute faced a trial by fire—literally. Before settling at its present-day perch, RPI’s academic hearth was nestled at the intersection of Sixth and State Streets in downtown Troy. However, on May 10th, a ferocious blaze, known as The Great Fire, devoured nearly 700 edifices in its path, including the twin structures housing RPI’s scholastic endeavors.

This fiery ordeal spurred a temporary diaspora, with the Institute seeking refuge in makeshift abodes for two ensuing years. Yet, from ashes rose determination: RPI soon transitioned to the freshly minted Main Building on Eighth Street, marking the commencement of its ascension up the hill to its now established domain.

This episode, although steeped in adversity, catalyzed a pivotal spatial transition in RPI’s 200-year saga, carving out a narrative of resilience and perpetual onward movement towards an enduring academic sanctum.

- 1862

Aniceto Garcia Menocal

Menocal came from Cuba to the U.S. to attend Rensselaer where he graduated in 1862.

Almost immediately he became assistant engineer and later chief engineer in charge of construction at the waterworks of Havana, Cuba. Menocal mapped the two most plausible routes for an interoceanic canal — initially working through the narrowest part of Nicaragua from 1872 to 1874. He favored a Nicaraguan canal, arguing that it possessed lower mountain passes and existing usable lakes and that a canal placed there would lie closer to American ports than one built across Panama. He staunchly opposed Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps plan for a sea-level waterway through Panama.

StoriesEventsJoin

Us